Mola mola, a fish so bizarre-looking that they named it twice. Mola, from the Latin for ‘millstone,’ is the scientific name for the Sunfish, one of three species in the Mola genus. In French and Spanish, the Sunfish is translated as ‘Moon Fish,’ in Chinese it’s the ‘Toppled Wheel Fish,’ and in German it’s known as the ‘Swimming Head,’ a term which certainly conveys a vivid image. Yet a casual Google image search will demonstrate that none of these names truly capture the sheer bizarreness of the fish’s appearance. Baby molas are described as ‘protected by a star-shaped, transparent covering that looks like someone put an alien head inside of a Christmas ornament’ and truly have to be seen to be believed.(1) And when they grow out of their ‘fry’ stage, the most well-known of the three species, the mola mola, holds the record as becoming the heaviest bony fish in the sea. Growing as large as 14ft by 10 ft, the largest one ever caught weighed in at over 5,000lbs – for reference that’s around the weight of a white rhino. And what do these curious-looking denizens of the deep eat to attain these incredible sizes? Jellyfish. Yes, you read that correctly – an ocean dweller that is between 96% and 97% water by weight. Confused? Let’s dive deeper…

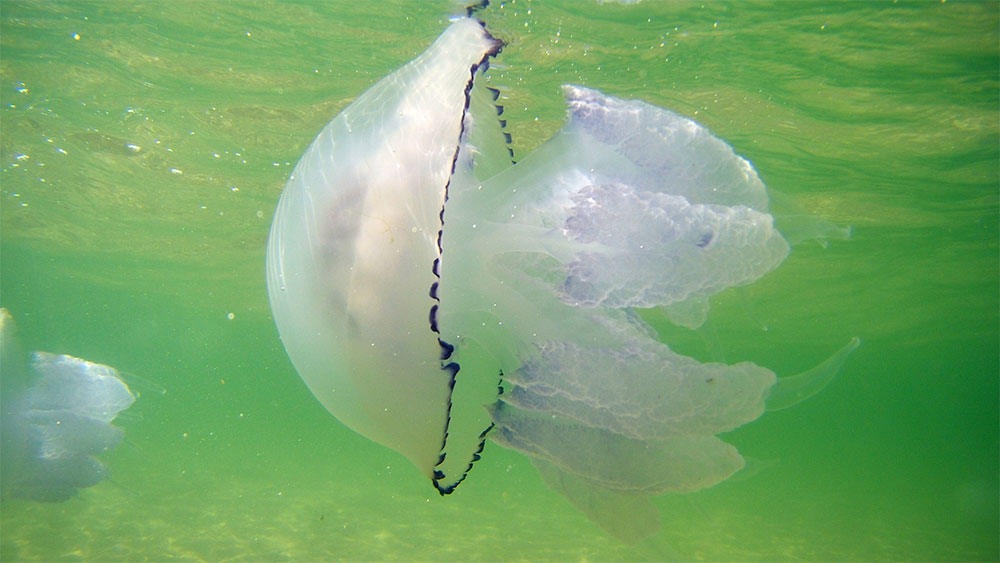

Jellyfish – or ‘jellies’ for brevity – are invertebrates of the biological phylum Cnidaria. One of the defining characteristics of this group of marine creatures, which includes sea anemones and corals, is their radial symmetry – a trait that allows the creature to detect the potential for food or threat from any direction. In evolutionary terms, jellies are remarkable in that, at over 500 million years old, they may be one the world’s oldest creatures – predating dinosaurs – but remain very simple organisms. Composed of three layers – the outer epidermis, the middle mesoglea, and the inner gastrodermis – the jellies lack a central nervous system, brain, heart, and blood. A nerve net – a very basic nervous system – allows the animal to respond to stimuli such as light and smell, and a dual function orifice serves as both a mouth and an anus. Let’s take a moment to ‘digest’ that particular fact…

OK, so while the above was perhaps not a deliciously palatable piece of trivia it is nonetheless true that jellies are very much an appetite stimulant for more than just the mola mola. While to the Western palate the idea of tucking into a diaphanous, mucus-secreting, jelly blob whose mouth doubles as its anus might not set the tastebuds tingling, jellyfish have been part of the Asian menu for millennia. Popular in China, Japan, and Korea, of the dozen or so species that are commonly fished for the restaurant markets, most are eaten when soaked in brine or dried and served with a strong tasting sauce accompaniment. In Vietnam, jellyfish season runs from April to June when giant jellyfish bloom just two or three miles offshore, giving street food vendors the opportunity to whip up batches of local delicacies such as jellyfish salad, salted jellyfish and jellyfish noodles.

But if you’re thinking of transitioning from hot dogs to jellyfish noodles, how nutritious could these snacks be? Let’s face it, only 3%-4% of each bite is anything other than water…

Well, the answer to the question of nutrition is…it depends. Each species is made up of a different class of compounds but the one common nutrient is collagen, a protein with anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant qualities. According to Dr. Antonella Leone of Italy’s CNR Institute of Sciences for Food Production, collagen produces peptides which can be very beneficial to human health. In an interview published in Food Navigator, Leone, a lead researcher in the Horizon 2020 program which is funded by the European Commission, noted that when digested ‘collagen produces several peptides [that can provide] anti-arthritic properties […] We are studying the effects of this small peptide on human cells to establish the real activity of proteins from jellyfish.’(2)

And it’s not just the nutrient profile for the jelly itself that comes into play. Micro-algae are contained within the body of jellies living in symbiosis with their host, and these are a very rich source of lipids – including those old favorites omega-3 and omega-6. So, alongside the collagen with its antioxidant peptides, those who tuck into the diner’s ‘Jelly of the Day Special’ will also get a boost in their essential fatty acid intake in a healthy low-cal meal.

So maybe on a nutritional level it makes sense to see jellies as part of a new array of protein options for a growing human world population. But are they a sustainable option?

Due to changing conditions in the Earth’s oceans – over-fishing, ocean warming, and nutrient runoff, for instance – the size of jellyfish populations may actually be on the increase, which is good news for the mola mola and also for others that rely on the jellies for their daily caloric intake. According to National Geographic, animals such as turtles, penguins, tuna, and albatross have made jellyfish the ‘snack food of the ocean.’(3). And in a scenario where we add them to our Western diet it’s also a net positive for us. Because of their feeding behavior, jellyfish are relatively easy to catch. Moving up to the surface to feast on phytoplankton, fish eggs, and small fish, they are traditionally caught in a technique more akin to skimming than trawling, so developing commercial fisheries dedicated to jellies could make good business sense. In Georgia and Florida, for instance, a prevalence of cannonball jellies (Stomolophus meleagris – also prosaically known as the ‘cabbagehead jellyfish’) allows an alternative catch for shrimpers whose season ends just as the jellies arrive. According to a report in Food Dive, ‘in the winter and spring months, a boat can fill its trawl net in five minutes and rake in 100,000 pounds of cannonball jellyfish a day. Some fishermen reportedly make up to $10,000 a day by jellyfish trawling.’(4)

And with those kinds of revenues in mind, it would be tempting for any fisherman to jump on the albeit wobbly bandwagon and get in on the action. But as with anything to do with food and public health, regulation must be in place to ensure safety. In regards to governmental oversight, the federal Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the agency that regulates fish and ‘fishery products’ here in the US. Under Title 21, Part 123, a ‘fish’ is defined as ‘fresh or saltwater finfish, crustaceans, other forms of aquatic animal life (including, but not limited to, alligator, frog, aquatic turtle, jellyfish, sea cucumber, and sea urchin and the roe of such animals) other than birds or mammals, and all mollusks, where such animal life is intended for human consumption.’(5) And given that jellyfish falls under that category catching, handling, processing, and storing of these invertebrates all fall under the same auspices as those for any other seafood. Which includes a comprehensive Hazard and Critical Control Points protocol, or HACCP.

In terms of fisheries, the FDA’s recommendation for a HACCP includes a full listing of food safety hazards for each fishery product.

This covers natural toxins or drug resides, microbiological or chemical contamination, pesticides and parasites, the risk of decomposition, the use of additives, and any physical hazards associated with the seafood. Moreover, Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) related to sanitation must also be written and implemented to protect the safety of the product from catch to sale. For instance, where water comes into contact with the product it must be deemed safe – this includes ice used for storage. To prevent cross contamination or contact contamination, general best practice protocols must always be followed to protect food contact surfaces from cleaning compounds, lubricants, fuel, chemical/biological/physical contaminants, sanitizing agents, and even condensate, and of course there’s the perennial clause on the exclusion of pests. Full operational records of sanitation control procedures should be maintained and are subject to inspection and review by the FDA.

At this point, although the regulations are complex (see Appendix 8: Procedures for Safe and Sanitary Processing and Importing of Fish and Fishery Products for full details) they are not unusual in their purview. What is different about the jellyfish HACCP and SOPs, however, is that each species of jellyfish caught requires different handling and conditions of storage and preservation if it is to be viable as a food source. As Dr. Rasa Slizyte of GoJelly partner SINTEF, Norway noted: “We should remember that jellyfish varies quite a lot from species to species, from one geographical location to another geographical location, and we would expect also seasonal variation. So before we start choosing the right processing method we need to know what we are working with.”(6) And given the already complex regulation in place, perhaps that off-season side gig for Florida’s shrimpers is not looking so attractive.

So perhaps instead of creating a culinary demand for jellies, catches could be exploited in a different way? Perhaps a by-product of the fish could be of more use than its meager flesh? Perhaps we need to talk about…mucus.

What makes jellies slimy? Mucus.

And when jellies are stressed they produce rather a lot of it, the main component of which is the glycoprotein mucin. Mucin is essentially a single protein chain polymer which is connected to oligosaccharide branches and it functions as an antimicrobial, an adsorbent, and a surfactant. And it is this capacity that the abovementioned GoJelly, an interdisciplinary and international initiative funded in part by research institutes, commercial fisheries, and the European Commission, has recognized the potential of jellyfish mucus as a solution to the problem of coastal and ocean pollution by plastics. With 16 teams in 9 countries, GoJelly is financed to the tune of around $6.8 million and has just completed its first year of a 4-year project to explore the exploitation of jellies not only for human and aquacultural food, but also for pharmaceutical and cosmetic use, and in combatting marine pollution. The concept of using the mucus in a biofilter to strain microplastics from water was born of the accidental discovery by French researchers in 2015 that the sticky substance could capture nanoparticles of gold in suspension. Dror Angel, lead researcher at the University of Haifa, Israel, later decided to see whether the same result could be achieved with microplastics. According to an article published this year in Hakai Magazine, a publication exploring ‘science, society, and the environment from a coastal perspective,’ in their tests the researchers ‘added jellyfish mucus to a suspension of microplastics, gave it a mix, and observed if the plastic beads adhered to the sticky mucus and sank to the bottom of the tube.’(7) Initially the tests were not completely successful until the team realized that the quality of the mucus from their jellies – the nomad jellyfish – was different from that used by the French researchers. Now with an eye to creating a biofilter for use in wastewater treatment plants, engineers at GoJelly are extracting mucus from a variety of species to discover which work best at capturing plastics at the nanoparticle and microparticle levels of filtration. Although current technologies leveraged at wastewater treatment facilities remove microbial and organic materials from effluent very efficiently, sifting out microplastics remains a challenge. Testing designs in three European seas (the Baltic, Mediterranean, and the Norwegian Sea) GoJelly’s prototypes will aim both to reduce the microplastic content of treated wastewater and also demonstrate that a market could be created for a jellyfish fishing industry.

Given that GoJelly is only one quarter of the way into its research, it will be extremely interesting to watch how the technology and processes develop.

The challenges faced by bringing this technology to market include not only practicalities such as determining the most efficient species for use and the best storage and processing methods, but also more overarching issues around scalability, sustainability, and standardization. Given that marine pollution is a global problem, a global solution is necessary – but getting everyone on the same page operationally is never an easy task. But with that said, we have to hope that with the creative innovation and international cooperation demonstrated by projects like GoJelly will shine a light and offer sufficient incentive before we all drown in the mess of our own making. Stay tuned…

Hungry? Would you be tempted by jellyfish salad? If not, are you more intrigued by the GoJelly biofilters? Let us know how jellyfish interest you!

References:

- https://blog.nature.org/science/2017/11/27/meet-the-magnificently-weird-mola-mola/

- https://www.fooddive.com/news/will-westerners-eat-jellyfish/560033/

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2019/01/many-ocean-creatures-surprisingly-eat-jellyfish/

- https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/Article/2019/07/30/Jellyfish-A-new-sustainable-nutritious-and-oyster-like-food-for-the-Western-world

- https://www.fda.gov/media/80431/download

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rEj6dxdLglI

- https://www.hakaimagazine.com/news/in-the-future-jellyfish-slime-may-be-the-solution-to-microplastic-pollution/

Pingback: Collagen Popcorn - Food Contact Surfaces

Pingback: Could Tobacco Be an Unexpected Ally in Killing COVID-19? - Cleanroom News | Berkshire Corporation

Pingback: Could Tobacco Be an Unexpected Ally in Killing COVID-19? - Cleanroom News | Berkshire Corporation