We’ve said it before but we’ll say it again, when it comes to de-stressing from the week, many folks like to kick back with a glass of wine, a chilled beer, or a creative cocktail. And unless it is medically contraindicated, drinking in moderation can be a pleasant and social experience. Assuming, of course, that the alcohol in question is free from tampering or contamination. However, recent reports from as far afield as the Dominican Republic, India, and China reveal a disturbing increase in bootleg booze, counterfeit cocktails, and toxic tipples. And then there’s also the matter of Moutai – a potent, fiery spirit once available only to China’s elite – which is sweeping the nation, despite being almost undrinakable. Reportedly tasting like the love-child of paint stripper and kerosene, what could be the attraction of this drink and what is the ‘contamination angle’? Let’s take a closer look…

Moutai – also spelled Moatai – is revered as China’s ‘national liquor.’

With a distilling workshop in the eponymous town within the Guizhou province dating back potentially to 1599, the beverage first came to prominence during the Ming dynasty. Inasmuch as ‘champagne’ is authentic only if it derives from the Champagne region of France, genuine Moutai is distilled only in this one small town in the Southwest of China. Raw ingredients such as sorghum, wheat, corn, and/or rice are fermented in a solid-state process using qu, a ‘starter’ that acts in the same way as yeast does for bread. During the course of a year, the fermenting mix is distilled seven times, with the final distillation stored for three or four years in earthenware jars. Once fully fermented, the grains are heated, the vapors collected, and the ensuing liquid is around 60% alcohol. A good Maotai is judged on color (bright glossiness and perfect transparency), aroma (from sweet and smooth to floral and fruity), and taste (full bodied and rich). And like a good Scotch or Bourbon, the experience of savoring Maotai exists along a spectrum. And some connoisseurs do not even taste the drink. Auctioneers Christie’s of London recently highlighted held a collector’s sale where commemoration Moatai was offered for between 28,000 and 50,000 Chinese Yuan, or $3983 and $7112, for a 500ml bottle.

All of which puts into (at least financial) perspective the current craze amongst drinkers in Shanghai who spend long hours in line for the opportunity to purchase their very own bottle of the white liquor for just 1,499 Chinese Yuan, or $213. The beverage, produced by Kweichow Moutai Co., the only designated state-owned distillery, has fast become a new symbol of affluence, even though non-aficionados describe its flavor as somewhere between kerosene and paint stripper. And that’s for the genuine article. Perhaps inevitably, the high price of Moutai has birthed a network of distillers, exporters and distributors across China looking to cash in by supplying counterfeit liquor. According to a report in SafeProof, an organization dedicated to raising awareness of the risks associated with fake or counterfeit alcohol, a multi-year investigation ended in the seizure and destruction of 7,488 bottles of counterfeit product.(1) With workshops spread across Beijing, Chongqing, Zhejang, Hunan, Guizhou and Renhuai, the production and distribution of illicit Moutai looks like it is becoming big business.

Moreover, China is not the only country to have a burgeoning black market devoted to peddling bootleg booze.

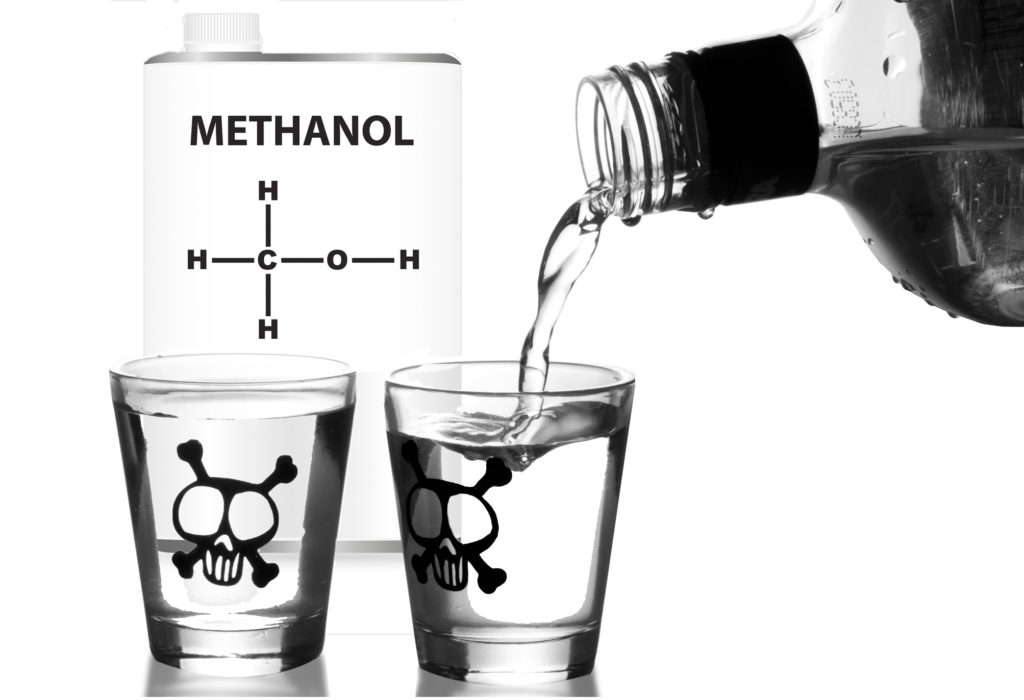

A National Public Radio (NPR) report published in February this year detailed the mass outbreak of alcohol poisoning in India in which some 200 people were hospitalized and a further 150 died after imbibing a tainted beverage. Given the relative poverty of many in India, brand-name alcohol is out of reach of large sections of the population and illegally-made hooch – or ‘country liquor’ – enjoys widespread popularity. ‘[A] type of bootleg booze you can buy in most villages: at a counter, by the glass, or in little plastic single-serving pouches. It’s much cheaper than branded, regulated alcohol. Sometimes it’s a brewed or fermented concoction similar to beer or wine; other times it’s distilled into spirits,’ – however, in order to increase its strength, the hooch can also be laced with additional substances, particularly toxins such as methyl alcohol, or methanol.(2)

According to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), an asset of the National Institutes of Health, methanol belongs to a group of chemicals known as ‘toxic alcohols,’ a cadre that also includes isopropyl alcohol and ethylene glycol.(3)

It is widely used as an industrial solvent – a carburetor cleaner, for instance – and a fuel source, for instance when keeping food warm. When ingested, methanol is absorbed directly into the total body water compartment and is ultimately metabolized by the liver, although initial metabolism begins with the conversion via oxidation of methanol to formaldehyde in the mucus membrane of the stomach. And when it is metabolized, methanol can result in difficulty breathing, blurred vision or blindness, low blood pressure, agitation and confusion, dizziness, headache, nausea and vomiting, seizures, and liver toxicity.

The treatment for methyl alcohol poisoning, according to MedlinePlus, an online source of health information developed by the NIH, is a battery of tests including blood and urine analysis, CT scan, chest x-rays, and electrocardiogram, followed by the administration of IV fluids and antidotes such as fomepizole or ethanol. However, multiple organs may be damaged by ingesting methanol and – in the case of liver damage – ongoing treatments such as dialysis may be required. Sadly, in the case of those poisoned in rural areas of India, poverty may preclude such expensive long-term care and result in negative outcomes.

Just over 9,000 miles away from India lies the Dominican Republic, a Caribbean nation originally home to the Taino-Arawak Indians before colonization by Christopher Columbus and the Spanish. Sharing the island of Hispaniola with Haiti, the Dominican Republic is now famed for its rainforest ecotourism, ceynote diving, canyoneering, iconic architecture, and vibrant night life. Recently however, it has also come to be associated with a sudden rash of tourist deaths, the cause of which is suspected alcohol contamination. According to an article in Vox, ten US tourists died and over a dozen more became ill after consuming drinks from their hotel’s minibar.(4) Centered on a small cluster of hotels, the deaths had much in common: survivors reported experiencing abdominal pain, sweating, and nausea, and having detected a strong ‘chemical smell’ in their rooms. Investigators are divided as to the provenance of the odor: some suggest the presence of methanol in contaminated beverages, while others are considering whether pesticides sprayed on local foliage could have been the culprit. According to a CNN report, two of the affected tourists noted a ‘maintenance person spraying palm plants that covered air conditioning units just outside their room’ before the onset of symptoms such as stomach cramps, drooling, incessant sweating, and dizziness.(5) All of these symptoms are associated with exposure to organophosphates – chemicals commonly found in commercial pesticides.

And chemicals used in pesticide and herbicide products seem to be an on-going problem.

In a Business Insider article published in February of this year, a study by US PIRG, a public interest research group, found that of 20 beverage samples tested for glyphosate, 19 contained the ingredient. Better known for its use in the weed killer Roundup, glyphosate is a non-selective herbicide, meaning that it kills plants indiscriminately, and in animals can lead to increased salivation, burns to the mouth and throat, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. With that said, in an article published in The Drinks Business, a news outlet for the drinks industry, toxicologist William Reeves estimated that a ‘125-pound adult would have to consume 308 gallons of wine per day, every day for life to reach the US Environmental Protection Agency’s glyphosate exposure limit for humans, assuming a level of 51.4ppb to begin with.’(6) It should be noted, however, that Reeves is a scientist working for Bayer, the parent company of Monsanto which created Roundup…

But suppose – just suppose – you are tee-total. Abstemious. A non-drinker. Are you safe from the toxic ingestion of methanol. One would assume so. But one would be wrong. In a shocking instance of product contamination last year, Lake Michigan Distilling Company of La Porte, IN, recalled its 95% Ethyl Alcohol product. Doing business as Ethanol Extraction, the company produced a solvent for use in the process of extracting and preserving essential oils from plants. According to the Tisserand Institute, dedicated to the promotion of essential oils from a place of scientific inquiry and clinical evidence, ethyl alcohol is widely used as an antimicrobial in a range of foods, beauty products, and medicines. Also known as ethanol, the chemical is basically made up of two parts carbon to six parts hydrogen and one part oxygen (C2H6O) and is created via fermentation (and subsequent distillation) of starchy vegetables such as beets, grains, and fruits. Moreover, in the essential oils field, in addition to its anti-microbial properties, it also acts as a solubilizer – allowing two substances (a solvent and a solute) to blend together. Think of the interaction of oil and water and you get the idea. However, when this ethanol is tainted with methanol an unsuspecting consumer is at risk. According to Consumer Affairs, a Massachusetts man died last year after ingesting the tainted product leading to the recall. However, it should be noted that the product, which was sold in 8oz, 1gallon, 2.5 gallon, and 5 gallon containers, was clearly labelled as not for human consumption and carried the warning ‘HARMFUL IF SWALLOWED. MAY CAUSE DAMAGE TO ORGANS.’(7) We are unsure as to the reason the victim chose to ingest the substance.

While it is possible to speculate on the reasons for the New England poisoning, other contaminants in alcoholic beverages may be harder to avoid. The filtering process for beer and wine, for instance, could potentially introduce toxic heavy metals into the product. Diatomaceous earth (DE), a sedimentary rock, is used a a clarifier and may contain cadmium, arsenic, or lead, and according to an article in Newsweek the amount of heavy metal contamination depends on several factors. The pH of the product makes a difference, as does the amount of filtration agent (DE) used. In a paper published in the Journal of Agricultural Food Chemistry, lead author Benjamin W. Redan writes that ‘[a] laboratory-scale filtration system was used to process unfiltered ale, lager, red wine, and white wine with three types of food-grade DE [and] resulted in significant (p < 0.05) increases of 11.2–13.7 μg/L iAs [inorganic arsenic] in the filtered beverage.’(8) Furthermore, the amount of DE used in the filtration system also contributed to the level of contamination: ‘There was a significant (p < 0.05) effect from the DE quantity used in filtration on the transfer of iAs in all beverage types […] Methods to wash DE using water, citric acid, or EDTA all significantly (p < 0.05) reduced iAs concentrations,’ concluding that ‘[t]hese data indicate that specific steps can be taken to limit heavy-metal transfer from DE filter aids to beer and wine.’(9)

So where does this leave those of us who enjoy an alcoholic beverage at the end of the week?

It may simply come down to arming ourselves with the facts and making a personal decision on what/whether/how much to imbibe. While incidents like those in India and the Dominican Republic remain comparatively rare, they do occur. However, it might be worth putting them into context. According to data from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, an initiative of the NIH, in 2017 Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) affected 14.1 million adults over the age of 18, with and estimated 88,000 deaths from alcohol-related causes annually. This makes AUD the third leading cause of mortality in the US, after tobacco use and malnutrition/sedentary lifestyle.(10) So although we should be aware of issues around the contamination of our favorite beverages, it might be worth leveraging our anxieties to support moderation in drinking rather than complete abstinence. Unless, of course, the only drink available is one containing a spirit that tastes like kerosene – in that case, we’ll stick to fruit juice!

Have you ever tried China’s ‘National Spirit’? Do you worry about contaminated cocktails or bootleg beers? We’d love to know your thoughts!

References:

- https://www.safeproof.org/china-moutai-liquor-counterfeit/

- https://www.npr.org/2019/02/23/697317095/bootleg-liquor-kills-scores-in-indias-latest-mass-outbreak-of-alcohol-poisoning

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482121/

- https://www.vox.com/the-goods/2019/6/26/18759843/dominican-republic-tourist-deaths

- https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/24/health/dominican-republic-sickness-deaths-invs/index.html

- https://www.thedrinksbusiness.com/2019/02/traces-of-weedkiller-chemical-found-in-beer-and-wine-brands/

- https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/ethanol-extraction-recalls-alcohol-product-because-possible-health-risk

- https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06062

- ibid

- https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-facts-and-statistics

Pingback: Alcohol Use in the Time of the Pandemic - Food Contact Surfaces

Pingback: Toxic Alcohols 101: Ethanol, Methanol, Isopropanol - Cleanroom News | Berkshire Corporation